Are commonly overlooked fossils escaping our notice due to a perception shift? Since 2014, Sam Dunlap, an artist and musician, has meticulously gathered specimens from New England and maritime Canada, alongside matching samples from Asia. Explore the fascinating world of these widespread fossils and join us on a journey of perception and discovery.

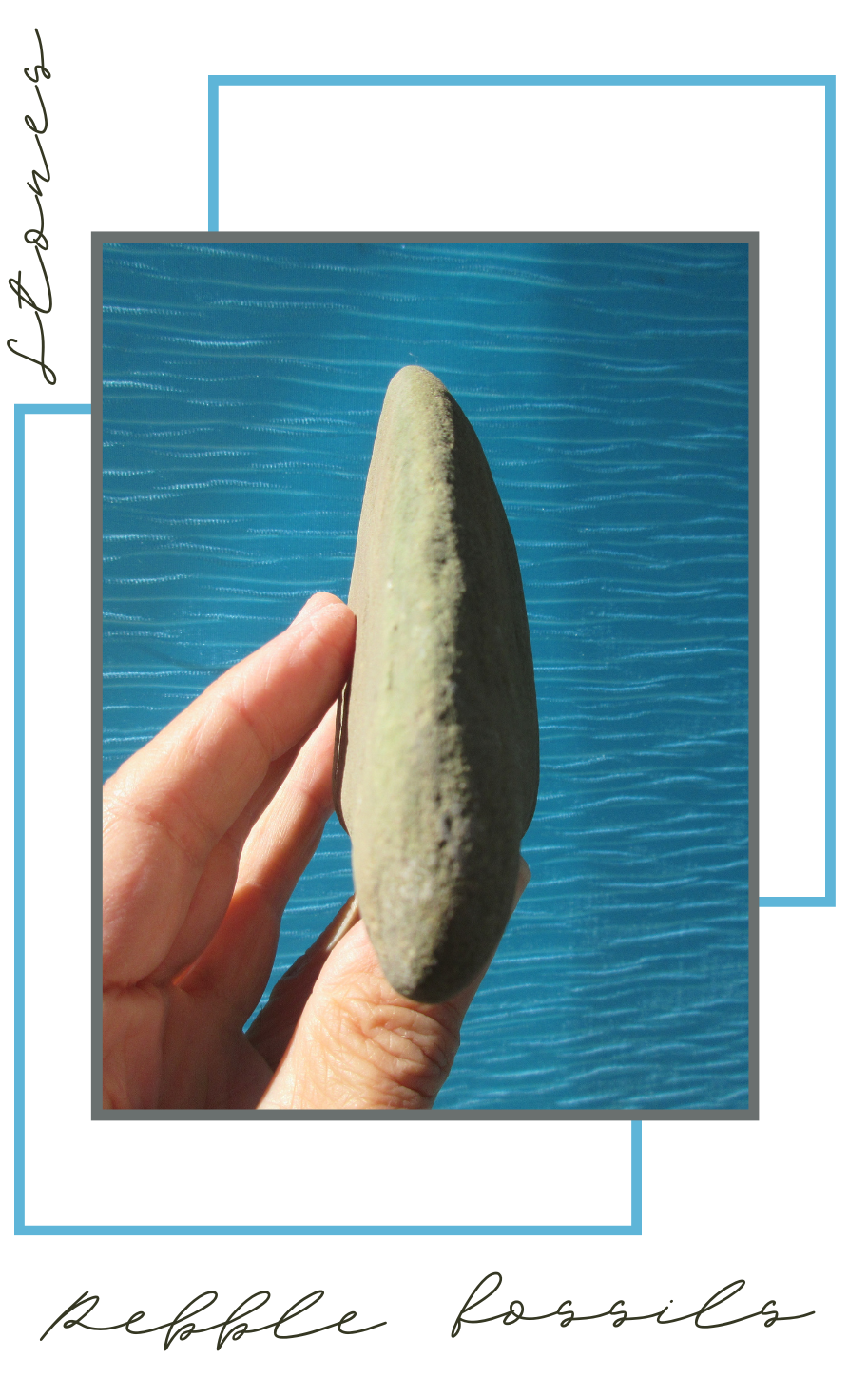

The proposition is these rocks are a kind of fossil. Because they posses the composition and structural organization of rocks, identifying evidence that they're fossils has been a challenge. How looking for these rocks became an ongoing project, and the way evidence of a fossil may be identified is included in the description of the project.

Logically, there is no way to prove that a rock isn't a rock. Even though examples might look like or include features that suggest a fossil, it wouldn't necessarily be evidence that it was anything but a rock. Proving otherwise was daunting. If it wasn't something about a rock, it had to be something about a fossil but I had noticed from the start that some examples were better than others, less degraded by abrasion or weathering. What I didn't appreciate was that most often, it wasn't that they were degraded, but actually deformed. The realization that deformity was a characteristic was a breakthrough. It was an effect which applied to almost all examples and yet was not related to the composition.

Because deformed examples could be identified, they could be used as a reference. That was a turning point in terms of evidence. Similar deformities that differed in mineral content suggested the form was other than a material artifact. What's more, the forms and deformed versions could be correlated as the same, presenting an unlikely coincidence. It suggested the effect was original and not as might be assumed, a rock sculpted by erosion. But the effect also opened the door to other possible evidence. Qualities such as surface features or grain patterns, that while rock-like, could be considered as possible evidence of a fossil.

Once visual appearance could be verified and fragments could be organized by category, all categories contained deformed versions with claw like forms. It was often the most deformed ones that were the most informative. A great many claw-like forms are deformed in similar ways, often having the appearance of a collapse to one side. Some of these are as if reduced to two dimensions but the longitudinal profile comparisons have shown that they remained intact. Another version that generally retains an accurate longitudinal profile looks like a bas-relief sculpture. These have a slumped pseudo 3D version on one side only.

Obviously not every rock is a fossil but if these are three dimensional facsimiles, a sign. of past life, it must have been a situation where minerals were transported by water, contained within the organic form and over time, crystallized. As a working hypothesis, the process could be described as having a colloidal precursor, a protein perhaps that between the time of life and crystallization as a rock, the colloidal stage was subject to the spacial compromise of a typically deformed example.

There are so many claw-like examples that these, too, might suggest the role of a protein. The crystallization of minerals within a colloidal lattice might also account for the same all over consistency of typical examples. There are exceptions but for the most part, the material is like a rock, not a mineral replacement of organic structure like the wood grain of petrified wood.

Why are so many examples visible at the surface in Maine? Could it all have been unearthed during the ice age? In that way is Maine a special case? Why do examples appear to be deposited and clustered in some places? In some locations, all rocks are rounded and in others, not so much. And of course, how could any of this remain recognizable?

I have collected examples in Maritime Canada to east as far as Prince Edward Island. And in PEI I found a few of the same dark gray/black shale-like examples that seem to be pretty much everywhere else. The next question then is what is to the east from there?

We know that both sides of the Atlantic Ocean were once in close proximity. The question is, might examples like those of Maine be found on the other side. If that could be confirmed, then Maine and its examples could be placed in a regional context. Answering that question would be, due to the acquired familiarity gained over the last ten years, straight forward. The plan is to go and find out.